In April of 2012 (see Policy Brief Volume 12, Number 20) we documented the work of a General Assembly appointed task force whose job was to either, (1) develop a statistical measure of assessment deviations from market that, if reached, would trigger a mandatory reassessment or (2) establish a maximum number of years a county could let pass before doing a reassessment. In both instances, the task force could not come to a conclusion other than to say more study is needed. Unfortunately, the task of addressing reassessments has not advanced beyond the task force report, leaving counties to decide when to reassess or when a lawsuit results in a court order to undertake a reassessment.

We noted last year that new reassessments are occurring in three western Pennsylvania counties that had gone quite a long time since last reassessing (see Policy Brief Volume 15, Number 43). Each of these will be the first reassessments in decades. In Washington County the first batch of notices for new values were slated to be mailed out in March.

In the case of Indiana County (previous reassessment was completed in 1968 and a new set of assessed values is to be certified in May), a consultant hired by the Board of Commissioners to evaluate their completed reassessment noted:

“In only Delaware, New York, and Pennsylvania is such a long interval between reassessments as Indiana County has experienced conceivable. Most states mandate reassessments annually or on a fixed cycle of no more than six years. In addition to the property tax inequities that accompany infrequent reassessments, assessment districts find it difficult to maintain mass appraisal skills and resources, including appropriately organized collections of essential data.”

This comes as no surprise. In our 2007 report and numerous times since then, we have pointed out and demonstrated the woeful inadequacies of the Commonwealth’s reassessment policy as it pertains to the frequency of reassessments. These inadequacies have been known for some time, and the task force did nothing to change it in 2012.

In 2013, new values went into effect in four counties: two were the result of court decisions (Allegheny and Lebanon) and two were done by county government decision (Erie and Lehigh). All four counties now utilize a 100 percent pre-determined ratio (this means that the assessed value is 100 percent of market value as opposed to some percentage less than 100, Lehigh was using a 50% ratio prior to 2013). Thus, in 2016, the new assessments will have been in effect for four fiscal years.

The table below shows the taxable assessed values for each county in each year since the reassessed values went into effect.

Taxable Property Values ($000,000s)

In terms of year-over-year change in taxable values, since 2013 the biggest increase was the 2 percent increase in Allegheny County (2015 to 2016) although the County’s total assessment is still below the 2013 value. All four counties have shown positive growth in taxable values in the past two years. Note that any growth in value that occurs in a period when there is no reassessment is attributable to new construction or appeals by taxing bodies.

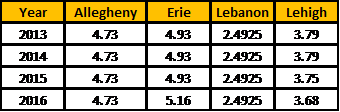

The following table shows the millage rates for county tax purposes in each year since 2013. The millage rates in Allegheny and Lebanon Counties have held steady since 2013, Erie’s increased 5 percent this year, and the rate in Lehigh has fallen twice in the past two years, a total of 3 percent. All counties had to comply with state laws requiring that in a reassessment year millage rates have to rollback to achieve revenue neutrality and then any increase to the millage rate would have to be enacted in a separate vote. Act 71 of 2005 applies to counties of the second class (Allegheny) and Act 93 of 2010 applies to counties of the second class A through eighth class. In years following the reassessment, counties are not subject to any state statutory limitation on increases.

Millage Rates

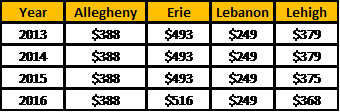

Here are the county real estate taxes paid on a home assessed at $100,000. Note that of the four counties only Allegheny County offers a homestead exemption for County tax purposes (Act 50 of 1998 carries out the Constitutional language of Article VIII, Section 2vi). The exemption was approved in a 1997 referendum that permits local taxing authorities to exempt a portion of assessed value for qualified homesteads and farmsteads. This is distinct from the homestead relief via slot machine gaming for school property tax purposes. Thus, a qualifying homestead assessed at $100,000 in Allegheny County is currently taxed upon $82,000 (the current homestead exemption is $18,000) while the other counties tax a $100,000 home at $100,000.

County Taxes on $100,000 Assessment

In terms of taxes paid, the owner of a $100,000 assessed home is paying the least amount of county taxes in Lebanon County, the most in Erie County. If the $100,000 was applied to property that did not qualify for the homestead exemption (for instance, let’s say the owner has a duplex worth that much buts rents both units out) the taxes in Allegheny County would be $473 for county purposes. Still not as much as the taxes in Erie County, but the gap between Allegheny and Lehigh County would grow. This Policy Brief does not examine the impact of municipal and school district taxes on total tax payments and what those levies would do to the relative gaps in total property taxes paid.

So can the data from the class of 2013’s assessments provide any guidance to counties currently in the process of reassessing? To be sure, there is always resistance to and argument against reassessment, but time and effort spent educating the public in advance about what their assessed value change means for their tax bill is key to reducing resistance and post reassessment angst. Property owners need to understand that windfall increases in taxing body revenue are limited to fairly small amounts and thus most of any change in their taxes post reassessment will be determined by the percentage change in their property value compared to the percentage changes in the total values of the county, the municipality and the school district in which they reside. Simply put, if a property’s assessment rises by 80 percent but the county increase is 110 percent, that property should see a decrease in its county tax bill. The same comparison would be done with the municipal and school district total assessed value changes.

A recent article on the Washington County reassessment says that the County envisions changing its millage rate to between 3 and 4 mills for 2017 based on 100 percent of 2015 market value. That’s a big change from the current use of just 25 percent of 1981 market value and a current millage of 24.9 mills. Imagine a home’s assessed value change going from $15,000 ($60,000 market value in 1981 prices) currently to $150,000 after reassessment and change in the ratio of assessment to market value to 100 percent from 25 percent.

While the dollar value jump appears astronomical (a tenfold increase) to the property owner, the resulting change in taxes based on current and anticipated county millage would be only 20 percent, rising from $375 to $450. If the county millage went to 4, the increase in county taxes would be to $525. And this would be a rare case. The expected change in millage rate needed to hold revenue neutral from the prior year suggests the County is looking for total assessed values to rise 8.3 times the current level.

Obviously, this hypothetical owner will not be happy, but of necessity there will be some owners getting a decreased county tax bill. And even though the owner might be somewhat unhappy, that’s quite a different and less frightening outcome than fierce opponents of reassessments harp about. No doubt there will be some properties whose assessments that will jump far more than 8.3 fold, but the obvious response is they have been under assessed and not paying their fair share of taxes based on true market value. But they can appeal to ensure accuracy, which should be the goal of any assessment process.

Without question, property owner knowledge of how a reassessment works and how the process of what determines their new tax bills along with frequent and regular reassessment would do wonders for Pennsylvania’s property tax system. Bringing it into the 20th century at least.